The NYT and me: a sad story of disillusionment, in three parts

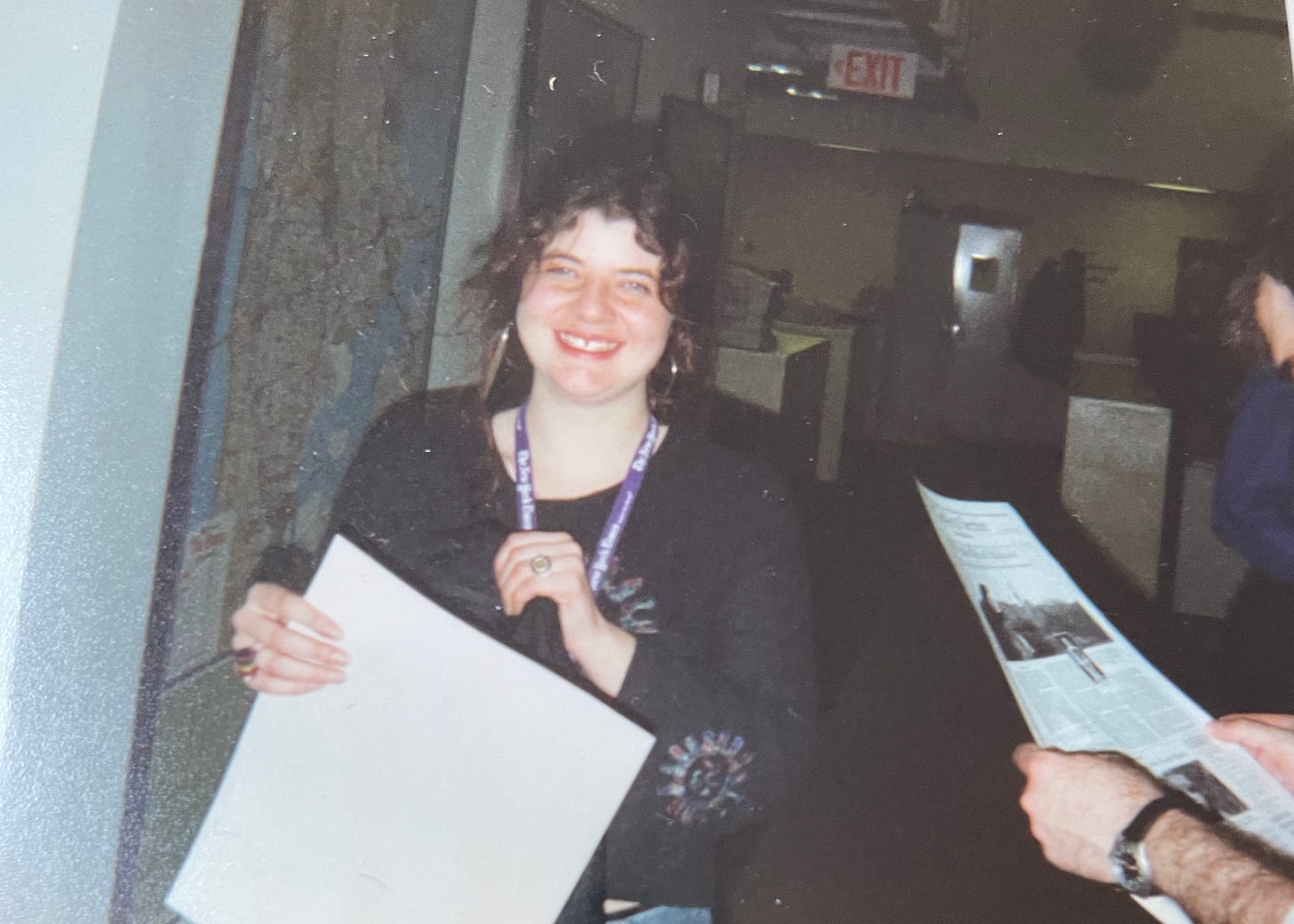

As a young woman I was lucky enough to work at the world's most famous newspaper...then things got complicated

If you like my work, please consider a paid subscription, or share it with a friend! If you hate my work, share it with your enemies!

Dear Readers,

This week’s Substack is a look back into the distant past — both personal and journalistic — to a time when I was a young woman working in the centre of a world-famous and important news organisation, at what was a pivotal moment in history before everything changed.

This story is both deeply personal, as it pertains to the arc of my adulthood and a painful experience I have never publicly discussed. But it’s also about an institution — The New York Times — that is part of the fabric of American society, for better or for worse.

Like most people in their 40’s, my life has been marked by ups and downs and personal and professional defeats. But more unusually, mine are entwined with the world’s most famous brand in news and one of its most damaging scandals.

That scandal is just one of many scandals detailed in a new book by American author and essayist Ashley Rindsberg, The Gray Lady Winked. The book dives into the overlooked history of misdeeds and misrepresentations by The New York Times in its writing, as journalists like to say, the first draft of history. A mutual friend put Ashley in touch and he sent me advance copy of the book in late 2020, a year in which my own view of the paper had shifted dramatically from admiration and implicit trust to shocked dismay.

This is is an essay that details my disillusionment with the Times as well as my personal experiences at the place: a sad story in three parts.

Part I

This part of the story, I should’ve written 17 years ago. But at the time I wanted to run as far away from it as humanly possible.

Anyone who was paying attention to American journalism in the early 2000’s will remember the name Jayson Blair. He was a young reporter at The New York Times who was unmasked as a liar and a plagiarist in 2003, at the height of the Iraq War. This was of fevered interest across the media world, because, of all the media companies across the planet, The New York Times stands alone in its mystique. A car-crash as spectacular as this one rarely comes along in the highest professional realm of any sector. When a company that is devoted to shining light on the dysfunction and malpractice of others is itself found to be guilty of those things, that company’s rivals are going to feast like buzzards over roadkill.

I started working as the dayside clerk1 the Metro desk of The New York Times in the spring of 1999. I was 23 years old, and it was my second job after university. For a period of less than a year following my arrival, Jayson Blair was my close friend and almost daily drinking buddy. It took about that length of time for me to realise that he was a deeply unstable and untrustworthy train wreck of a man with a bad drinking problem. I ended the friendship, which caused drama for a while — him showing up at my apartment late at night, or coming uninvited to social gatherings where I was and having to be forced to leave; the kind of the thing that isn’t uncommon in a time of life when partying and working are the main activities. But the storm calmed after a while and I forgot about him. Jayson and I continued working for the same section of the newspaper for another couple of years without incident, and in 2002 I left the Times with a plan to go travelling then return to the US to work as a reporter at a smaller paper — which I did, ending up at a newspaper in Rhode Island later that year. That should have been that.

Except it wasn’t. The very same character flaws and destructive behaviours I saw during our friendship drove him, just a few years later, to commit professional suicide in the most public of ways. What would otherwise have been the sad unravelling of a young addict became news, because it involved The New York Times. He was exposed as a serial liar and plagiarist who was allowed to run amok over multiple high-profile national stories. And even though our friendship had long expired by that point, and I was no longer even working at the paper when his infamy became national news, I was briefly dragged back into his orbit. In 2004, he published a book which purported to give his side of the story, but in reality was a trashy, score-settling, exercise in myth-making in which he was the victim of heartless bosses. And I was a central supporting character.

For someone who had nothing to do with the actual story, I was nonetheless vastly overrepresented in his book. And while Blair had earned his public shaming, my personal humiliation was just collateral damage.

I remember the moment I received the call at my new job, from a friend who still worked at the Times, informing me that Blair’s book was out, and that I was indeed featured in it. I was so horrified I slid off my seat and hid in the darkness under my desk, leaving my fellow reporters to wonder what on earth was wrong with me.

I followed the coverage closely. One review singled out Blair’s inclusion of me in the book. Mortified, I emailed the reviewer, and he kindly responded:

“It must be an awful thing to have a former friend burn you in this way, but your only real error was trusting a probable sociopath. And you weren’t alone in that regard.Reading between the lines, I’d guess you were a standout in the newsroom and that Blair was pretty sweet on you. You also stand out in his book, as you have no doubt noticed. Though at times it seems like his narrative is stalking you, you’re mostly associated with the few good times he has to write about. Oddly, Jenny, you may be the book’s most likeable character. Small comfort, I’m sure.”

It was a small comfort — though I still appreciate that a stranger took the time to send me comforting words.

A friend emailed me sections of the book in February 2004, which I then sent on to my father — a well-known author and journalist who was also mentioned by name in Blair’s book. Apart from the false and deeply embarrassing claims Blair made about our personal relationship (mischaracterising it as more than a brief platonic friendship), Blair’s naming of my father was especially gratuitous and hurtful. My father at that point had a reputation built on nearly 30 years as a professional writer and highly regarded journalist and commentator. Within Irish and Irish-American circles he was very well known. Other than the fact that I had known Jayson, he had no connection to the Blair scandal. Though deep down I’m sure he realised that the contents of a young fabricator’s obscure book would not matter much in the long run, in the moment he reacted with fury and deep concern. I recently came across these emails, which my father had apparently printed out and kept in a file, dated 25 February 2004.

The date is significant to me— because less than a month later, my father was diagnosed with cancer. By May, my father was dead.

Once my father’s illness became known, Blair became insignificant to us— helped by the fact that his book was a commercial and critical failure, and there was no social media to keep the story alive in perpetuity. And so the whole saga became a sad and tawdry footnote to an otherwise tragic time of life for me — one that saw not only the death of my beloved father, mentor and professional role model, but also the end of my career in journalism.

Always a sanguine and rational man, having his daughter’s honour impugned pushed my father to a state of anger I had never seen him in, and given how I lost him so soon after, it is burned into my memory. The night I received the email with passages in the book about me, I sat in my car outside my office, in the freezing New England winter fog, talking my father down from the ledge as he fulminated about wanting to sue Blair. As upset as I was, I realised this was a rash suggestion that was very out of character for my father, a man who in his own life and career had been subject to threats and lies from genuinely dangerous men and had reacted to them with equanimity. I was totally unaccustomed to hearing my father loose his cool, something he did not do even when facing his own imminent death a few months later. I distinctly remember the dread and desolation I felt that cold February night. It felt in that moment like the beginning of the end of something that I loved very much, and it was.

Part II

The end of my career in journalism did not have any direct connection to Blair’s book and its lies about me. While Blair did use his version of me as a vehicle to badmouth the editors we both worked for, in conversations that he invented to suit his book’s agenda, I have never once thought that directly contributed to me not getting hired by any other newspapers after the scandal. Very few people read the book. It is much more likely that my lack of success was part of a much bigger, industry-wide job die-off that was I just unlucky to get caught up in. I started out in newspapers just as their business model was being eviscerated by the Internet. My first full reporting job, which is where I was working when the scandal erupted, came just as Facebook was being invented. The times they were a-changin’.

My three years at The New York Times remain a highlight of my professional life. I’m not exaggerating when I say I looked forward to going into work every day I worked there. The editors for whom I worked on the Metro desk were distant in the beginning, but once I proved myself as capable and enthusiastic they almost universally took the time to encourage, support and develop whatever raw talent I had. The reporters were friendly, down-to-earth and grateful that I was good enough at my job that it helped them do theirs. I felt lucky every day I was there. I don’t have a single bad memory of the place.

From a managerial perspective, the Times I saw was at the top of its game. When I was first hired, in May 1999, I was given a full week of paid training just on their editing software system — away from the newsroom, with a person whose job it was to teach me, one-on-one. After that week, I shadowed another clerk for a full month before I was left to do the job alone. Never again would I work for an organisation that had the resources to devote so much time and human capital to a single low-level employee. After that, most publications I worked for were ramshackle, catch-as-catch-can places where morale was low and everyone muddled through as best they could with the shrinking budgets they had.

There was some cynical grumbling and jockeying, of course. But the pride that staff had in their work at The Times was a beautiful thing to behold — the shared sense of mission was a unifying force that would make any corporate management consultant envious. Despite the fact that there was this particular dysfunctional, destructive employee buzzing around the place, the vast majority of men and women I came across were consummate professionals and very, very good at what they did. And that made for a pretty happy environment.

When I left Metro in 2002, I went out on a high note, with a stack of glowing references and the goodwill of all the editors and reporters I had worked with, who threw me parties and lunches and showered me with going-away gifts. I had written a slew of features, contributed to their Pulitzer-winning 9/11 coverage, been sent to work in the Washington DC bureau during the Gore-Bush election, and built real friendships, some of which continue to this day.

So why am I bringing up the sad story of my generally insignificant and otherwise forgotten involvement and in the Blair scandal?

Part III

The last part of this story would have been impossible to write 17 years ago.

Late last year, a friend got in touch to tell me about a book written by a mutual friend, presenting a devastating look at a side of The Times that I did not see. The author, Ashley Rindsberg, sent me a copy of the book, The Gray Lady Winked, which is coming out in early May.

It presents a picture of the paper that is altogether different from the rosy one I remember from 20 years ago. But it is one that matches my current perception of the Times as having abandoned all pretence to objectivity and transformed itself into a very effective advocacy shop for progressivism.

I can’t pinpoint the exact moment I lost faith in the Paper of Record, but in my humble opinion its coverage last year of both COVID and the Biden campaign were derelictions of professionalism so grave they border on treasonous.

First was the Bari Weiss debacle — in which a centrist opinion writer, hired for her centrist opinions, was drummed out of the paper for writing centrist opinions. Weiss, it seemed, violated the new core tenet of the paper: be as woke as possible.

Then it was the inappropriate editorialising , the misleading language, and bizarrely oblique handling of what would otherwise be major scandals (I’m looking at you, Hunter Biden laptop story). An irony here is that 20 years ago, I managed to impress my editors and reporters on Metro with what they called my ability to recognise what made a good story — it was just an innate sense I had. I knew what tips (and there were many) had legs without anyone having to take the time to explain it to me. Sometimes I think about those folks and I wonder, do they really, genuinely, in their heart-of-hearts think Hunter Biden’s deals in China and the Ukraine, his crack habit, his taking business trips on the government dime, were not particularly newsworthy — in a year when his father was running for president? Sometimes I can almost hear those old hands whispering, like ghosts of forgotten times, trapped in an attic: “If you believe Joe had no stake in his son’s profiting off the Biden name, I have a several bridges in Brooklyn to sell you.” These were the worldly men and women who taught me the phrase “if your mother says she loves you, check it out.”

But maybe I’m the crazy one.

Until I read The Gray Lady Winked, I was under the impression — naively — that this was a new development at the paper. That it wasn’t an institutional problem but rather part of a broad cultural trend in which almost all elite organisations and cultural touchstones feel they must capitulate in every way to the Neo-racism of critical race theory.

But Rindsberg’s book shows that the Times has been used by its owners as a tool to maintain its elite status and ingratiate itself with the order of the day since the beginning of the twentieth century.

What an eye-opener. Rindsberg’s deep-dive into the paper’s publicly available archive provided enough material to shake the faith of even the most loyal Times fan. For example: did you know that the Times Berlin bureau chief was so openly sympathetic to Hitler, that when his American journalist peers were rounded up for internment by the Nazis in 1941, he was allowed to remain in the comfort of a hotel because of his “proved friendliness to Germany”? The book outlines a decade of appalling reporting failures on Hitler, perhaps the most outrageous of which was their acceptance of the German propaganda that their attack on Poland was an act of self-defence and that Poland had, in fact, invaded first.

Rindsberg starts with the Nazis but ends with the 1619 Project, touching on most if not all of the major historical events in between. Rindsberg quotes at length the many criticisms made by a host of prominent historians who essentially demolished the Times’ portrayal of slavery and the creation of the American nation. Even one supportive historian who was used as a source for the project later said her views were misrepresented by the Times in its concerted effort to put its malevolent spin on US history.

I have spoken to Rindsberg a few times about his book, and provided a blurb for it. He describes the company as totally unaccountable — controlled as it is by a wildly wealthy family (the Sulzbergers) who have passed power down “male heir to male heir…they are the oldest or one of the oldest institutional patriarchies in existence today,” he told me.

Wokeness being the new religion of the nation’s upper castes, to borrow John McWhorter’s observation, it would make sense that The New York Times would throw itself wholesale into its prickly embrace. Because more than anything else, Rindsberg says, the Sulzberger family has used the paper as a means to remain firmly in the bosom of the elites — whether it be by flattering Hitler (and thus gain acceptance among WASP powerbroker in the 1920’s and ’30’s) or by rewriting American history to appease today’s powerful neo-Maoists.

In our current climate of intense polarisation and deep uncertainty over a multitude of grave threats, not having a trustworthy paper of record to provide us with sound information and reasoned analysis has to be one of the most significant and urgent problems we face. I certainly don’t want to claim that every item published in the Times is inaccurate, or that every employee has a sinister agenda: earlier this year, a long article about the Smith College debacle showed the nuance and fairness that I remembered. But overall the paper’s leadership has shown such terrible judgment on such big and very serious issues that it simply casts a shadow of doubt over everything else they now do. My trust is irrevocably shattered. What a waste. What a loss.

But mostly I marvel at the stark contrast between my experience working there 20 years ago and what I see the paper as now. It just goes to show how close you can be to a story, person or event and still not see it fully. While youthful naivety and untrustworthy memory may well play a part, I think the bigger reason for this discrepancy is due to my relatively lowly position on a desk that did not have the cachet of, say, the Magazine or the Editorial page or the Foreign Desk. Metro — while it was a reporting powerhouse in the local market — was by and for the plebes in the sense that it competed against the tabloids for scoops about cops and eccentric locals. It wasn’t within the purview of mahogany-panelled boardrooms and diplomatic functions. I certainly don’t recall ever seeing the elder Sulzberger grace our section of the newsroom. Though I did exchange words with him once, in the cafeteria, when a button on the skirt I was wearing got caught in the turnstile. He — stuck behind me — suggested I would have to take the skirt off to free myself.

One problem with journalists, and it is one I’ve seen up close several times, is their tendency to indulge in self-aggrandising fantasies of the hero and saviour, warrior for truth. Young dreamers used to be balanced out by hard-drinking, gnarly old newshounds whose approach to the job was more blue-collar than blue-state. Those guys are long gone. So the more idealistic strivers, of whom Jayson Blair was once one, now seem to have the upper hand. As he wrote in his application to the Times internship that would lead his permanent position at the paper:

'I've seen some who like to abuse the power they have been entrusted with,'' he wrote. ''My kindred spirits are the ones who became journalists because they wanted to help people.'

Of course, as inevitably happens to all idealists, today’s journalists have clearly curdled into something far more opportunistic and destructive. That energy is being harnessed and put into the service of a cynical strategy by those at the very highest echelons of global power. The result is dangerous, far-reaching and utterly corrupt.

The arc of my life took me away from newspapers, but, it turns out, not from narratives. I have used the skills honed at the Times to earn a living ever since I left the paper nearly 20 years ago — for that I am immensely grateful, still. And while I spent a long time grieving over the loss of a career I thought I wanted, now, when I look at what the industry has become, I feel nothing other than relief that I escaped.

If you like my work, please consider a paid subscription, or share it with a friend! If you hate my work, share it with your enemies!

Clerks were a fixture in The New York Times newsrooms until recently. Usually they were young people with journalistic ambitions who performed some administrative tasks but also served an editorial function. In my case, this was to answer the very busy phone lines into which hundreds of New Yorkers would call on a daily basis. My shift was early on in the paper’s daily schedule, when the editors were deciding what to put in the next day’s paper and assigning stories to reporters. Occasionally, a caller would pass on great stories which I would then send on to editors and reporters. The job was seen as a stepping-stone to greater things.

This is a brilliant essay. Thank you, Jenny.

The NY Times, like the Ivy Leagues, Rhodes Scholars, Time Magazine, 60 Minutes.... were all set up purposely with the intent to deceive humanity, it takes experience and tacit knowledge to figure that out.

Lots of Sociopaths out there, bipolar and now a life coach, Jayson has blank eyes, no one home.